As the world’s two most populous countries, India and China, battle it out for superpower status, the Indian Ocean is growing in prominence as a key geopolitical region. But human memory is short when compared with the history of humankind. Archaeological evidence has unearthed a number of insights indicating that this Indian Ocean connection has been a key region of cultural interaction and trade for approximately 2,000 years.

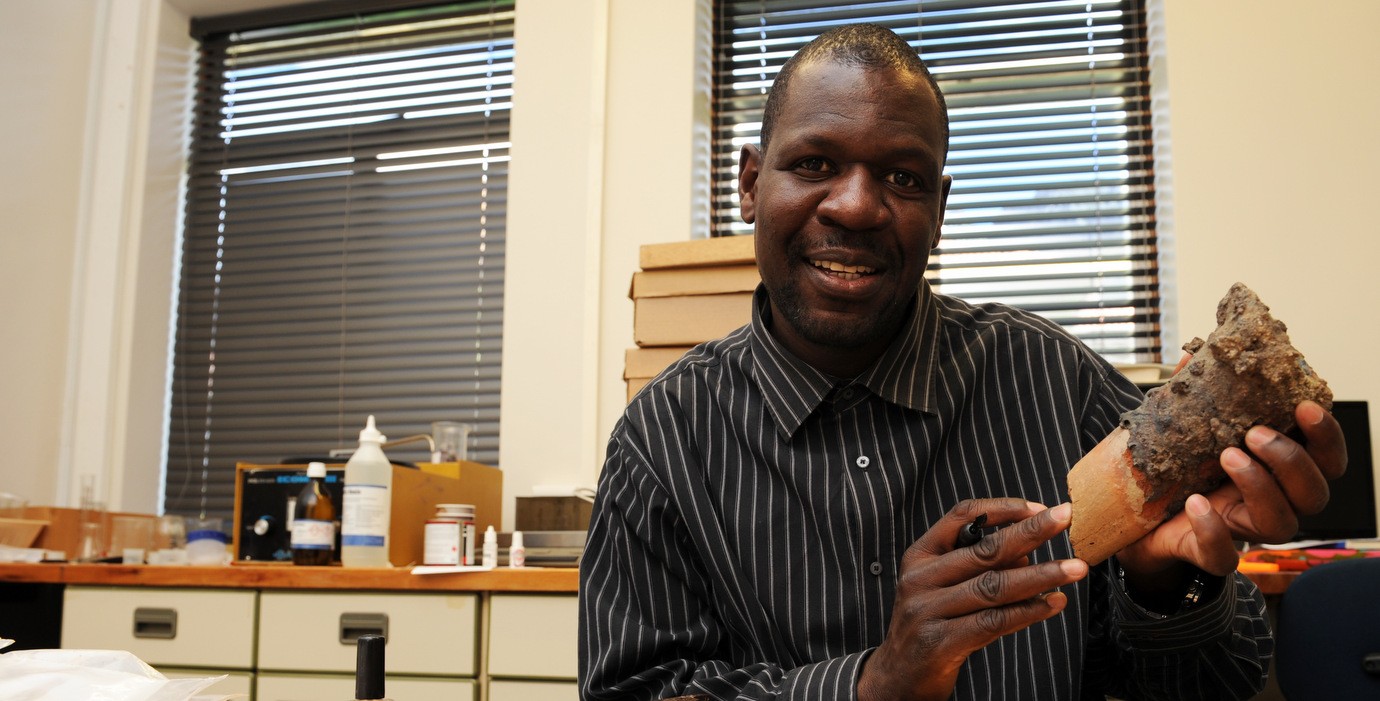

A team of WUN experts, which goes by the Indian Ocean Archaeology Network, is exploring the long-term history of trade and interaction across this geopolitical corridor to answer a key question: how did African plants and animals get to India? Dr Shadreck Chirikure, Associate Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cape Town, is one of the many WUN researchers searching for an answer.

“This initiative aims to uncover the long-term history of trade and cultural interaction within this strategic geopolitical corridor,” says Dr Chirikure. “There are some crops and animals that we know originated in India, but today can be found in Europe and Africa. Similarly, we find African plants and animals in India. What was the history? How did they get there?”

Through the network, archaeologists working within this region—which includes East Africa, and stretches up the Persian Gulf past India to China, and down to Australia—can now link up existing projects and build a framework for collaboration that might build a more complete understanding of its past. Dr Chirikure’s research, for example, focuses on the interior of Southern Africa, specifically Great Zimbabwe and Mapungubwe, and the connections between the hinterland and the coastal regions. While the network primarily focuses on sea links, Dr Chirikure believes it is important to acknowledge that those sea links were supported by land links that played an integral role in trade.

“It is from the inland areas that 99% of those commodities traded actually come. Gold was traded in East Africa, for instance; but that gold came from the interior. My research seeks to understand how it was mined, produced and traded,” he says. He also notes that while most of our knowledge is acquired from the Western world, archaeological evidence proves that mining, production and commodity trading were taking place in Africa prior to Western intervention—activities that researchers are only just beginning to learn about.

When asked how the network has benefitted his own research, Dr Chirikure said it has allowed him to interact and collaborate with researchers he probably would have never met otherwise.

“We may all be archaeologists, but we use different techniques and methods. We generally attend conferences and network within specific niches. However, through WUN, we met with a variety of researchers in the field, which allowed for great networking opportunities,” he says.

An important outcome of this was Dr Chirikure’s collaboration with Professor Mark Horton, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Bristol. Together, the pair will map out Great Zimbabwe using geophysical techniques with equipment from the University of Bristol.

“It is often through the more ‘out-of-the-box’ or unlikely collaborations that the best work is done,” says Dr Chirikure. “WUN’s contribution to this kind of research is thus invaluable.”

Archaeology, with its long timeframes, can offer broad insight into the many challenges facing humankind today. Initiatives like the Indian Ocean Archaeology Network can help researchers understand how humans faced similar challenges of changing environments and natural disasters in the past, so that we might tackle important issues such as climate change.

Read more about the WUN Indian Ocean Archaeology Network project.