Many of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) focus on basic needs, such as poverty, hunger, health, energy, water and sanitation. But if you assume that means science, engineering and medicine are the only disciplines needed to bring about real progress, you’d be wrong, says Stuart Taberner, Professor of German at the University of Leeds.

Look down the list of SDGs, he says, and you’ll see many others that focus on wider issues, such as peace, justice, equality, human rights and partnership working. For these, science alone can’t be the answer, or even the starting point. In fact, he argues, science can’t provide a complete solution to any of the SDGs, which is why arts and humanities is essential in all areas of development.

“Arts and humanities research is about people and places – and so is development,” he explains. “For example, a vaccine against a disease may work in any human being – it’s not limited to one country or region. But how people respond to an opportunity to take a vaccine, how widespread take up is and therefore how effective it can be, is very much dependent on people and place, and that’s where the arts and humanities, working closely with the social sciences, are vitally important.”

Professor Taberner cites the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, which began in 2014, as an example. Huge medical resources were mobilised to try and contain the epidemic and yet transmission rates remained high. What ultimately made the difference was an understanding of how West African burial practices were impacting on efforts to contain the disease – and these kinds of subjects, essentially culture and social practices, fall squarely within arts and humanities.

“There’s increasing recognition within science, engineering and medicine that arts and humanities involvement in development projects is essential,” says Professor Taberner. “Arts and humanities researchers can help build the understanding that’s needed to ensure money is spent well, in places and ways that will be most efficient, creating positive change that will be accepted by local communities.”

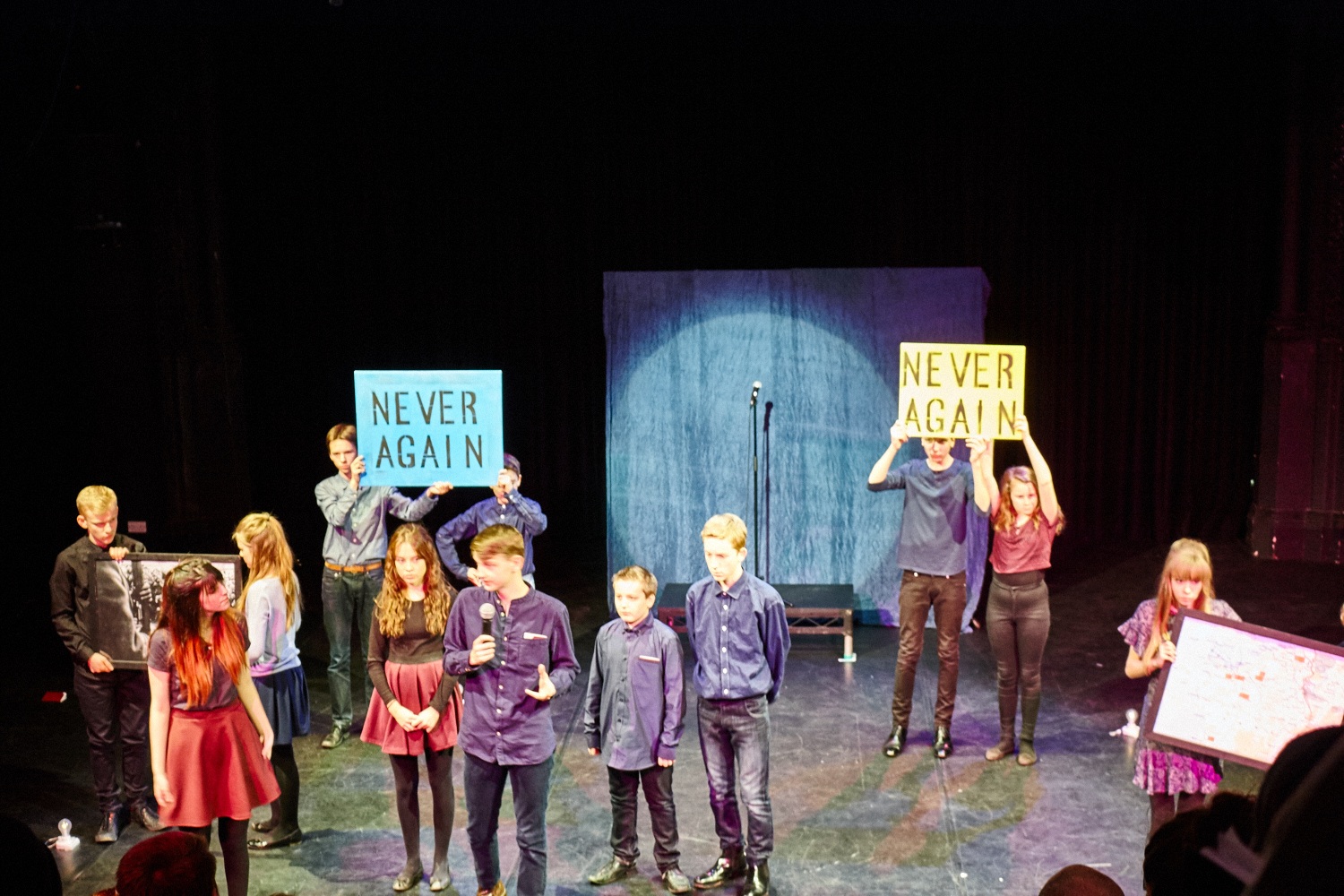

SDG 16 – peace, justice and strong institutions – is where Professor Taberner’s own work fits most comfortably. His research into how Germany has confronted its past, in particular the horrors of the Holocaust, led to a touring exhibition in South Africa, a country also coming to terms with a difficult history. The exhibition, a collaboration with the South African Genocide and Holocaust Foundation, looked at issues of shame, guilt and reconciliation. Shown in both museums and schools, it explored how Germany was able to build new institutions and rethink its national identity. The exhibition, in some cases, prompted the first discussions between black and white schoolchildren on whether South Africa is dealing with its own apartheid past in the right way.

“Historical research can feed into and influence modern day debates in developing countries,” says Professor Taberner. “Our work with the Foundation is helping it to be more of a campaigning organisation on human rights rather than simply a museum. We are now working with them on their education outreach on the Rwanda genocide, which was effectively Africa’s holocaust, helping them to shape a programme that has relevance to human rights debates in South Africa and across Africa as a whole.”

The work of Professor Taberner’s colleague in the Faculty, Professor Paul Cooke, provides a further example of research that would fall under SDG16 – although the institutions he’s helping to build are at a very grassroots level. Professor Cooke has been working across a number of countries helping disadvantaged groups to make their voices heard through films about the issues they face. In South Africa, this involved working with a charity and local arts organisation to enable township children affected by HIV/AIDS to make films on issues such as bullying, drug and alcohol abuse and xenophobia. The work has a further practical outcome: airing their concerns through the films has led the children to take an active role in the charity’s youth committees – a necessary step for the charity to access crucial funding to continue its work.

Professor Taberner believes projects like these should convince sometimes unsure arts and humanities researchers that they have a role and an impact in development projects. Currently seconded to RCUK as Director of International and Interdisciplinary Research, with particular responsibility for the Research Councils’ planning and delivery of the Global Challenges Research Fund, Professor Taberner is well placed to see how collaboration between all disciplines is essential for the development process.

”Arts and humanities scholars are now beginning to realise for themselves just how vital their research is for development,” he says. “The acceptance from other disciplines is there, though there may still be misunderstanding about what arts and humanities can bring to the table. Now the onus is on the arts and humanities to take up the challenge, show what we can do and make a real difference to development and the SDGs.”