The first images of motor proteins in action were published in the journal Nature Communications on Monday 14 September 2015.

These proteins are vital to complex life, forming the transport infrastructure that allows different parts of cells to specialise in particular functions. Until now, the way they move has never been directly observed.

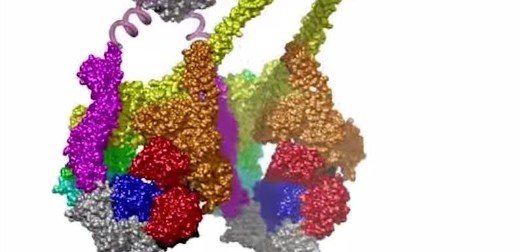

Researchers at the University of Leeds and in Japan used electron microscopes to capture images of the largest type of motor protein, called dynein, during the act of stepping along its molecular track.

Dr Stan Burgess, at the University of Leeds’ School of Molecular and Cellular Biology, who led the research team, said: “Dynein has two identical motors tied together and it moves along a molecular track called a microtubule. It drives itself along the track by alternately grabbing hold of a binding site, executing a power stroke, then letting go, like a person swinging on monkey bars.

“Previously, dynein movement had only been tracked by attaching fluorescent molecules to the proteins and observing the fluorescence using very powerful light microscopes. It was a bit like tracking vehicles from space with GPS. It told us where they were, their speed and for how long they ran, stopped and so on, but we couldn’t see the molecules in action themselves. These are the first images of these vital processes.”

An understanding of motor proteins is important to medical research because of their fundamental role in complex cellular life. Many viruses hijack motor proteins to hitch a ride to the nucleus for replication. Cell division is driven by motor proteins and so insights into their mechanics could be relevant to cancer research. Some motor neurone diseases are also associated with disruption of motor protein traffic.

The team at Leeds, working within the world-leading Astbury Centre for Structural Molecular Biology, combined purified microtubules with purified dynein motors and added the chemical fuel ATP (adenosine triphosphate) to power the motor.

Dr Hiroshi Imai, now Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Chuo University, Japan, carried out the experiments while working at the University of Leeds.

He explained: “We set the dyneins running along their tracks and then we froze them in ‘mid-stride’ by cooling them at about a million degrees a second, fast enough to prevent the water from forming ice crystals as it solidified. Then using a cryo-electron microscope we took many thousands of images of the motors caught during the act of stepping. By combining many images of individual motors, we were able to sharpen up our picture of the dynein and build up a dynamic idea of how it moved. It is a bit like figuring out how to swing along monkey bars by studying photographs of many people swinging on them.”

Dr Burgess said: “Our most striking discovery was the existence of a hinge between the long, thin stalk and the ‘grappling hook’, like the wrist between a human arm and hand. This allows a lot of variation in the angle of attachment of the motor to its track.

“Each of the two arms of a dynein motor protein is about 25 nanometres (0.000025 millimetre) long, while the binding sites it attaches to are only 8 nanometres apart. That means dynein can reach not only the next rung but the one after that and the one after that and appears to give it flexibility in how it moves along the ‘track’.”

Dynein is not only the biggest but also the most versatile of the motor proteins in living cells and, like all motor proteins, is vital to life. Motor proteins transport cargoes and hold many cellular components in position within the cell. For instance, dynein is responsible for carrying messages from the tips of active nerve cells back to the nucleus and these messages keep the nerve cells alive.

Co-author Peter Knight, Professor of Molecular Contractility in the University of Leeds’ School of Molecular and Cellular Biology, said: “If a cell is like a city, these are like the truckers on its road and rail networks. If you didn’t have a transport system, you couldn’t have specialised regions. Every part of the cell would be doing the same thing and that would mean you could not have complex life.”

“Dynein is the multi-purpose vehicle of cellular transport. Other motor proteins, called kinesins and myosins, are much smaller and have specific functions, but dynein can turn its hand to a lot of different of functions,” Professor Knight said.

For instance, in the motor neurone connecting the central nervous system to the big toe—which is a single cell a metre long— dynein provides the transport from the toe back to the nucleus. Another vital role is in the movement of cells.

Dr Burgess said: “During brain development, neurones must crawl into their correct position and dynein molecules in this instance grab hold of the nucleus and pull it along with the moving mass of the cell. If they didn’t, the nucleus would be left behind and the cytoplasm would crawl away.”

The study involved researchers from the University of Leeds and Japan’s Waseda and Osaka universities, as well as the Quantitative Biology Center at Japan’s Riken research institute and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). The research was funded by the Human Frontiers Science Program and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

The study used powerful electron microscopes at the University of Leeds’ Astbury Centre for Structural Molecular Biology. The University has since announced a £17 million investment in state-of-the-art facilities that will allow even closer observation of life within cells. New equipment includes two 300 kilovolt (kV) electron microscopes (EM) and a 950 megahertz (MHz) nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer alongside existing 120kV and 200kV EMs, and 500, 600 and 750 MHz NMR machines.

Dr Burgess and Professor Knight are available for interview.

Contact: Chris Bunting, Senior Press Officer, University of Leeds; phone: 0113 343 2049 or email c.j.bunting@leeds.ac.uk

The full paper: H. Imai etc., ‘Large-scale flexibility in cytoplasmic dynein stepping along the microtubule, is published in Nature Communications (DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9179).